The race to digitise language records of the Pacific region before it is too late

Languages are complex systems that encode knowledge of the world developed over many years. Small groups or tribes evolve unique ways of being, which each in their own way tell us something of what it means to be human

Nick Thieberger, The University of Melbourne

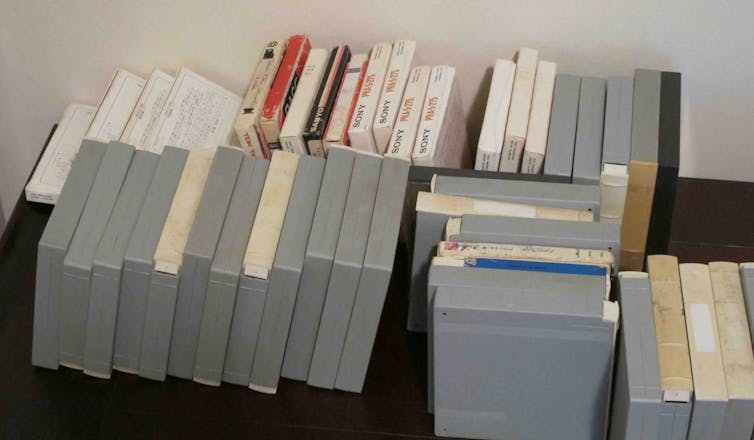

A suitcase of reel-to-reel audio tapes arrived recently at the School of Languages and Linguistics at the University of Melbourne. They were from Madang, in Papua New Guinea (PNG), were made in the 1960s and some contain the only known records of some of the languages of PNG.

There are very few records of most of the 800 or so languages in PNG, so every new resource is important. Languages are complex systems that encode knowledge of the world developed over many years. Small groups or tribes evolve unique ways of being, which each in their own way tell us something of what it means to be human.

Several years of sleuthing and negotiating have led to this moment when the tapes will be digitised and archived in Australia. The digital versions will be returned to Madang.

The team that has worked on this are from the Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures (PARADISEC), a research project based at Sydney, Melbourne and ANU that has been running since 2003.

PARADISEC has found and digitised more than 5,600 hours of recordings in 900 languages, and has built the digital infrastructure for linguists and musicologists to safely house the priceless recordings they make in the course of their research.

While the research importance of these recordings is enormous (some are the only recording for a particular language), the archive also provides access for the people recorded and for their families and communities, thus helping Australia to be a good neighbour to the Pacific region.

The recordings contain narratives, songs, conversation – whatever was able to be recorded at the time. The tapes we look for are those made by researchers using audio recorders and occasionally making movies, technology that was available from the 1950s.

In the past, little emphasis was placed on the importance of these primary materials. Collections of tapes were not cared for and, when the researcher died, they were sometimes left in personal collections for an executor to deal with.

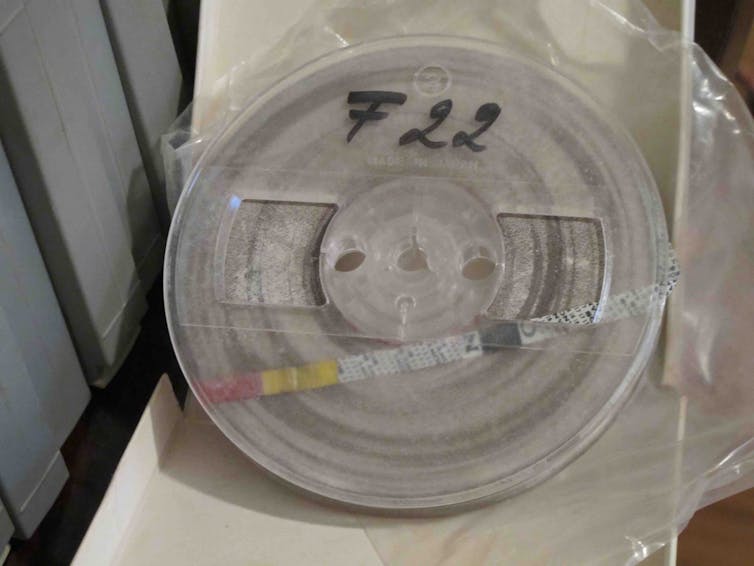

If the tapes were stored in humid conditions, they could get mouldy, as you can see in the image (below), and can then take some effort to clean and get ready to be played.

Oral traditions

The recordings that do exist can be used to relearn traditions. For oral cultures, there are no libraries to go to when you want to find out what your ancestors knew, but recordings of those ancestors can help reconnect with this oral tradition.

When the 2004 tsunami wiped out whole communities in Aceh, some languages and musical traditions were the unnoticed victims. PARADISEC has recordings of language and musical performance made along the west coast of Aceh in the 1980s in communities that no longer exist after the tsunami.

But languages are not just lost through natural disasters. More often major languages impose themselves, typically in colonial contexts where little choice is available to speakers of minority languages.

The affection keenly felt for a language is replaced by chagrin at its loss and then by some joy at discovering recordings that have kept aspects of the language alive. Once digitised, they are on the web, often as the only available online source for the language.

Uncovering the unknown

In among the audio in PARADISEC are recordings that have no descriptions. If there’s nothing written on the tape box, and we know it is important from the context of other tapes, then these files can be put online in the hope that someone will let us know what they contain.

Listen to these short snippets for a taste of the range of recordings we hold.

Bert Voorhoeve (collector), Bert Voorhoeve (recorder), Dina & Noguy (speaker), 1967; BA 4 1966 (28) PARADISEC Catalog, CC BY-NC-SA313 KB (download)

This recording is most likely in the Ba language.

Stephen (S A ) Wurm (collector), Helen Wurm (depositor); Continuation of Story 2. PARADISEC Catalog, CC BY-NC-SA313 KB (download)

This recording is in a language of the Solomon Islands.

Unknown singing, Solomons Museum (collector), 1974. PARADISEC Catalog, CC BY-NC-SA313 KB (download)

This recording is from the Solomon Islands Museum. All we know about it is that it contains singing.

Putting digital files on the web (with whatever access conditions the depositors require) means that they can be found by those most interested in them, typically the speakers themselves or their families.

Mobile phones are now available in even the most remote parts of the region and are owned by at least 80% of people in Vanuatu and 94% in PNG. Accessing the internet in this way means that we make files available in formats that save on bandwidth. We also provide as much of a description of them as we can to make them findable.

The humanities telescope

PARADISEC is essentially a multi-institutional collaborative humanities experiment. Think of it as the humanities equivalent of a radio-telescope for astronomy, but focusing on the cultures of the Earth rather than on the stars.

In many ways, we know more about the range and number of objects in space than we do about the thousands of languages and cultures around us.

But, while the telescopes are run by a few specialists and their output is comprehensible to only another few, as with much humanities research the work of exploring human cultural diversity is more understandable to all.

PARADISEC is part of the new face of the humanities but is constantly looking to find funds to do this work. In a race against time, many more collections need to be identified and preserved while we can still play the tapes. This work gives the cultures of our region the respect they deserve.

Nick Thieberger, ARC Future Fellow in Language Documentation and a Chief Investigator in the Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.